In the basement of what is now Swansea Museum, Hugh Mahoney and his family once lived in a row of tiny, dark rooms. Above ground, the father of four worked as caretaker for some of Wales’s most distinguished gentlemen - that is, until his troubles caught up with him.

This week, discover how one Irishman’s money problems led to tragedy at sea and an extraordinary new life in Australia.

Catch you on Sunday! Andrew

The Royal Institution and Its Gentlemen

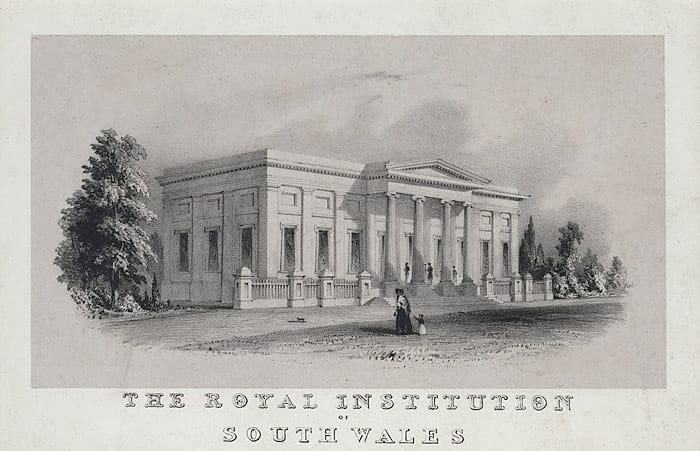

The Royal Institution of South Wales | Credit: National Museum Wales

Founded in 1835, the Royal Institution of South Wales aimed to put Swansea on the map as a centre of scientific learning and culture. Originally called the Swansea Philosophical and Literary Society, it started in rooms above a shop in Castle Square.

When Irish immigrant Hugh Mahony began working there in 1836, he was employed under an organisation that was basically a private club for some of Wales’ wealthiest industrialists and the intellectual elite.

Amongst other members, Lewis Dillwyn owned the Cambrian Pottery and lived at Sketty Hall; John Henry Vivian was MP for Swansea and owned the massive Hafod Copper Works, and Sir William Robert Grove was busy inventing the fuel cell.

In 1840, the society moved into a grand new building - what is now Swansea Museum. Part of it became Wales's first purpose-built museum, but it was only opened to the public twice a year at Whitsun, when thousands would flood in.

The rest of the time it served as the society’s headquarters with lecture halls, laboratories, and meeting rooms.

A lecture theatre at the Royal Institution of South Wales | Credit: Swansea Museum

Mahoney’s job was to keep everything running smoothly - cleaning specimens, stuffing animals, buying coal, maintaining the building, and managing the grounds. He worked from 9am to 10pm.

He also loaned out library books, managed membership cards, oversaw lectures and singing lessons, and more. As an 1841 agreement put it, Mahoney "stipulates to give the whole of his time to the business of the Institution, as sub-curator and keeper."

He was clearly a respected worker, as the Institution’s council initially praised his “intelligence, assiduity, and general good conduct.”

Life in the Basement

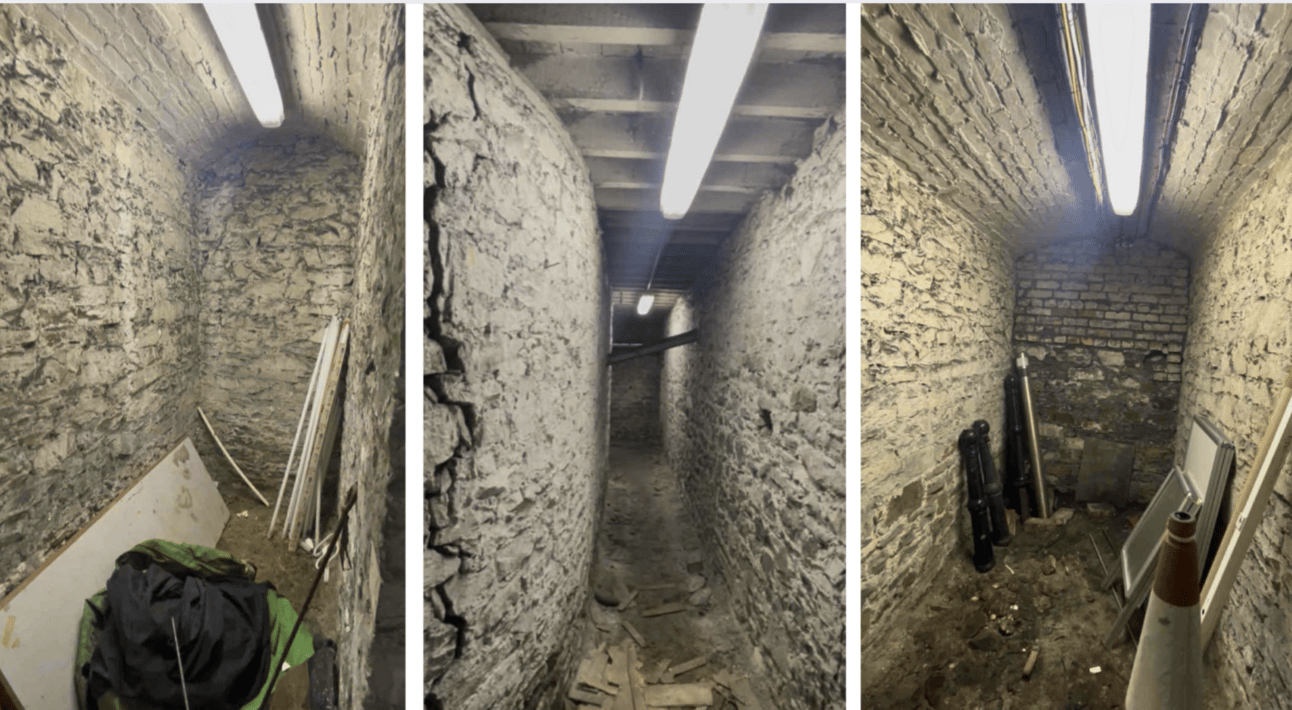

“Apartments” in Swansea Museum’s basement (images 1 & 3) pictured today.

When Mahoney moved into the museum in 1841, he found himself in an unusual living situation. He, his wife Elizabeth (a Swansea local), and their young children - Honora, Eleanor, and Elizabeth - occupied four rooms in the basement. The Institution’s 1841 agreement described these as “apartments in the basement, with coals and candles, and a salary of £1 per week.”

But as you can see from the image above (taken in 2025), the “apartments” were little more than narrow archways, not 5ft wide and 10 ft deep - claustrophobic, windowless rooms surrounded by damp, narrow corridors.

Despite this, Mahoney was actually better off than most Irish immigrants. He was part of a massive wave of Irish migration to the UK, driven by poverty and the looming potato famine that would soon devastate Ireland.

A fireplace in Swansea Museum’s basement, visible today

In 1839, before moving into the museum, census data shows he had lived in rented accommodation on the outskirts of town, in the area between Greenhill and Cwmbwrla - one of several districts where Swansea’s growing Irish population was settling.

Drawn by jobs in the booming copper industry and docks in Swansea, many found themselves crammed into poorly built houses with no sanitation.

By 1851, over 519,000 Irish-born people lived in England and Wales, many crowded into single cellars, with rooms subdivided with nothing but hanging sheets.

When Everything Went Wrong

Mahoney had been trying to supplement his museum income for years. In 1840, newspaper reports show he'd secured a 75-year lease on half an acre of land with permission to build a house, and by 1850 his family had moved to "Town Hill" Farm while he continued working at the museum.

But his troubles began to mount in the late 1840s. In 1848, he found himself in court charged with assault after a violent altercation where stones were thrown at him and he struck someone with his stick - he was fined 15 shillings plus costs.

Mahoney’s court summons, Cardiff and Merthyr Guardian - Saturday 09 November 1850

Mahoney’s financial situation then appears to have become desperate. In 1850, he was declared an insolvent debtor (essentially bankrupt), with an official assignee appointed to take possession of his estate - but the reasons for his financial collapse remain unclear.

The final blow came in May 1851. At a council meeting, Mahoney admitted to taking £34.13s (thirty-four pounds and thirteen shillings) of his employers’ money - equivalent to over £6,000 today - which he promised he would pay back. The council debated what to do with him.

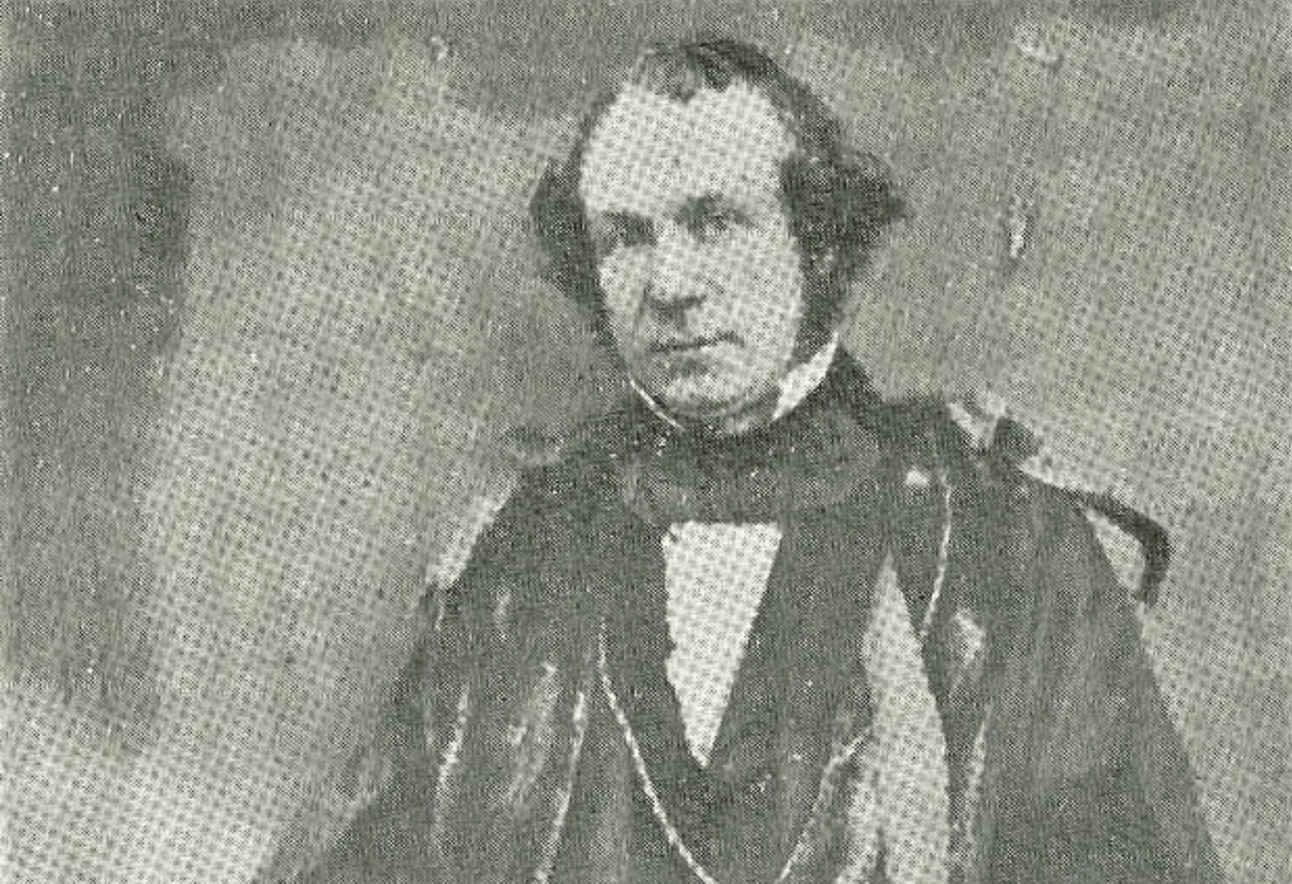

George Grant Francis dressed in his mayoral robes, 1854 | Credit: Wikitree

Some members came to his defence, including the Institution’s president and the local Catholic priest, who argued that there were extenuating circumstances.

But others, led by George Grant Francis - Vice President of the Royal Institution of South Wales and Mayor of Swansea (1853-54) - who lived next door to the museum and had long complained about Mahoney - argued for dismissal. Francis had previously called a special meeting to accuse Mahoney of using “improper language” towards him as far back as 1842.

Mahoney’s Irish Catholic background may not have helped his case either. By the 1850s, anti-Irish sentiment was rising sharply across Britain, fuelled by mass immigration during the Irish famine, religious prejudice, and fears over jobs, housing, and public health. In that climate, sympathy for a struggling Irish caretaker may have been in short supply.

Mahoney was dismissed. After 15 years of service, his time at the Royal Institution was over.

A New Life in Australia

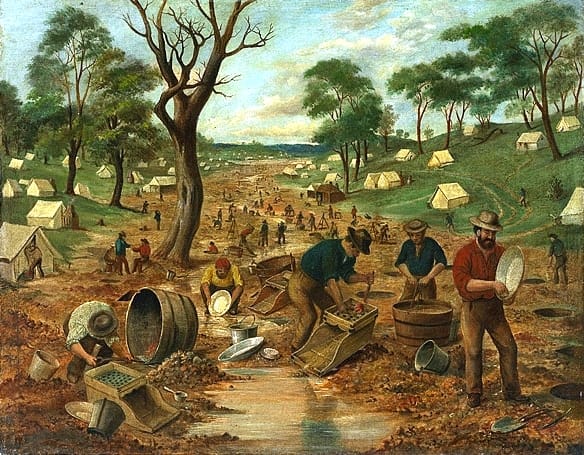

Over a year later in August 1852, Mahoney made a life-changing decision - to join the thousands of people emigrating to Australia, where gold had recently been discovered. A great Gold Rush was on, and free passages were available for settlers willing to make the journey to the colonies.

However, Mahoney’s journey to Australia was marked by tragedy from the start. He and his family sailed from Liverpool on August 27th, 1852, aboard the America - a ship that would become notorious for its terrible conditions and poor treatment of passengers.

During the voyage, his wife Elizabeth gave birth to a child, but neither she nor the baby survived. Elizabeth died several weeks later and was buried at sea, leaving Hugh to arrive in Moreton Bay (now Brisbane) on January 10th, 1853, as a widower - by that time, with seven children.

Australian gold diggings, by Edwin Stocqueler, c. 1855 | Image credit: Wikipedia

Despite this devastating start, Hugh rebuilt his life in the Australian wilderness. He became a timber getter, cutting cedar trees in what’s now the Canungra area of Queensland. By the 1860s, he was one of the first European settlers in the region’s hinterland - exploring virgin territory away from the coast and other established towns - a proper pioneer!

Hugh eventually became a successful tobacco farmer, selecting land under the Sugar and Coffee Regulations and establishing a property he named “Coburg.” When he died in August 1886 at the age of 90, local newspapers described him as “about the oldest settler in the district” and noted he had “reached the patriarchal age”.

Mahoney’s life story reads like a Victorian novel - from lowly caretaker to Australian tobacco pioneer. The basement of the Royal Institution must have felt like a lifetime away.

A huge thanks to Karl Morgan, Exhibitions Officer at Swansea Museum for inviting us to explore the building’s basement and inspiring the topic of this article!

Visit to Swansea Museum this summer holidays for free Unnatural History workshops every Thursday throughout August, plus free Summer Games! Its current exhibitions include Swansea's experience of WW2 and VE Day, and the Cockle Women of Penclawdd.

Love the Scoop? Support Us for £2 🦢

If you enjoy the Swansea Scoop and look forward to reading it every week, please consider supporting our work for just £2 per month through Buy Me A Coffee - or contribute with a one-off donation of any amount.

Your generosity helps to keep the Scoop going, and makes the hours of research and writing all worth it 😊

A big thanks to our 32 supporters so far, including our latest members, Steffi, Saranne, and Liz!

Sources

Monmouthshire Merlin - Saturday 12 June 1841

Cardiff and Merthyr Guardian - Saturday 09 November 1850

Swansea and Glamorgan Herald - Wednesday 19 March 1851

Swansea and Glamorgan Herald - Wednesday 14 June 1848

Welshman - Friday 16 October 1840